A gap in trust

A gap in trust

When customers complain, they expect that the people to whom they speak will be able to handle it. But this can only happen if our organisations trust customer service agents to use their judgement, initiative and discretion to do so.

But this is rare.

How do we know it’s rare?

Because too many times the agent has to hide behind phrases like: “…it’s our policy, I’m afraid,” or “…these are the only options I can offer you,” or “…let me speak to my supervisor.”

In other words, our people could resolve the problem, but our policy and procedures get in the way.

Why do we do this? Because we don’t trust our people.

- We don’t trust them to do the right thing, so we constrain them by procedures.

- We don’t trust them to do what is necessary to fix things, so we require them to escalate to supervisors.

- We don’t trust them to make the right decisions, so we remove their discretion.

Our agents become a barrier between the customer and resolution of their problem. Worse, agents know this, so they feel frustrated and grumpy.

Does the customer pick up on this? Of course they do.

So, instead of making things better for the customer, we make it more likely that we will make an already unhappy customer even more unhappy.

The trust trade-off

Yes, of course, there is a need to have consistent processes so that we can offer consistent standards of service quality. And, yes, I know that service is a cost and we need to make sure that we manage our costs with discipline and attention. And yes, of course, we know that if we give our agents free rein, we might incur liabilities and risks which may not be acceptable.

So we accept these constraints. And we require that our people work to them.

And by doing so, we assume that value we gain in meeting these needs outweighs the damage these constraints cause to trust: damage to our trust in our people, and damage to our customers’ trust in our brand.

And yet. And yet…

A different trust model

Is giving agents discretion over customer interactions very different from offering a quibble-free guarantee for returns as offered by (say) Marks and Spencers, Lands’ End or (most famously) Zappos?

Not in intent. Yes, such guarantees open these organisations up to abuse, but their success shows that losses through abuse are more than outweighed by the increase in brand perception, trust – and sales.

Perhaps we need to think about this trust thing differently.

So come on. If we want customers to trust us, then maybe we need to think about trusting the people we employ to work with customers to make things better.

Trust is earned – so let’s earn it.

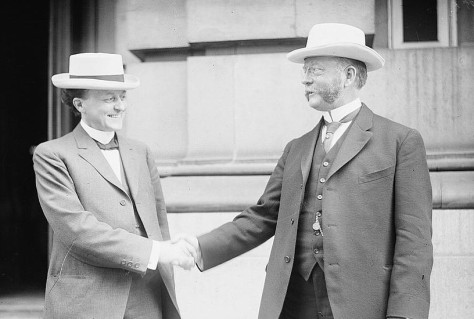

(Image credit: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress), Senator Atlee Pomerene meets first US Secretary of Commerce, William Cox Redfield, c.1910).