The cult of metrics can get in the way of delivering value.

The cult of metrics can get in the way of delivering value.

A little while ago – 1988, according to the OED – people started using the word ‘metrics’ in the way we use it today. Businesses took up the term, motivated by a belief that they needed to measure things if they were to manage business performance.

Of course, businesses have always measured what they do. But the advent of lean thinking, global competition and, most of all, the growing adoption of computers and spreadsheets all about this time meant that an organisation that lacked firm control of their business would be (and were) killed off by competitors who had learned to run tighter ships.

So, metrics.

And since then? On the back of Kaplan and Norton’s balanced scorecard (a good thing), Key Performance Indicators (KPIs*) (via Mack Hanan in 1970), Statistical Process Control (SPC) (also a good thing), Six Sigma (a good thing in the right place), Management Information Systems (MIS), Business Intelligence (BI), data analytics, dashboards and now, Big Data, metrics have become an industry. Many businesses employ phalanxes of analysts and banks of computers to ‘crunch the numbers’.

Now in many organisations, the first response to a proposal to do something new or better is “…how will you measure it?” (And not, you’ll notice, “…why do we want to do this?”)

This is a shame.

In business, the things we do, we do because they are important and will make a difference: to our organisation, to our customers, to our people. What we want to achieve, the value we are aiming to get, is much more important than how we choose to measure it.

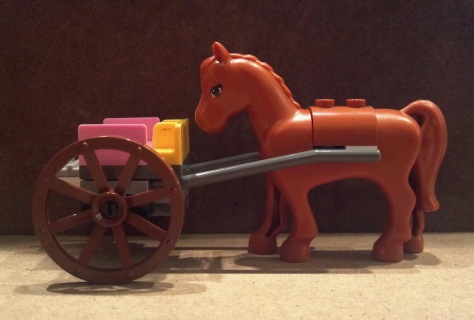

Yet too many organisations put the metrics cart before the value horse.

Important things get slowed down – or stopped – because we can’t agree on what metrics to use, or we need to wait to set up a reporting mechanism, or we are waiting for our technical people to “…set up the system” so it can measure and report.

The effect is that important things get lost, or are delayed, and the cost of doing business goes up.

Worse, we end up delivering projects that meet their metrics but miss their goal.

In extreme cases, metrics can become a madness that infects almost every business conversation. I once found myself working in an organisation that had 43,000 metrics in place.

Yes, they had the madness so badly that they had measured their metrics.

*Sigh*

Yet here’s the thing. The purpose of metrics isn’t to measure something. Their purpose is to give decision-makers a way to pay attention to something important in our business, over time.

But people can only pay attention to about seven things at a time. Any organisation has a core of a few things to which it needs to pay attention just to keep things going. Money, for example, or customers, or the amount of work we need to do, or quality, or risk.

If we can only pay attention to seven things, we have only a little room to pay attention to anything else: the things we need to change or make better. We need to pick these things to which we want to pay attention very carefully if we want them to succeed. They need to be important.

And if we have to pick our way through hundreds or thousands of metrics, then we can’t focus on these one or two important things. Or if, by some monumental effort of concentration, we can focus on these one or two things, we can only do so for a moment, before we are distracted by something else.

This is one reason why so many important initiatives hit the sand; why ‘Top Management attention’ is so transitory; why we lose sight of our goals in the middle of projects – because too many things are competing for corporate attention.

This is not to say that we don’t need metrics. On the contrary, having the right metrics against good standards with effective, practical and timely mechanisms for reporting them, is more of an imperative than ever. The argument for keeping tight control of business essentials is much stronger now than it ever was in 1988.

We have to begin the conversation about metrics differently. Perhaps we should start by asking what do we need to pay attention to, and why do we need to do so? If we can only play attention to seven things, what are the seven in which we want to invest our time and attention?

The dirty little secret of metrics is this: if they don’t help us to pay attention to the things that are important, then they are a distraction, and are stopping us from running our business properly.

For the key to getting things done in business isn’t to measure things – it is to pay attention to them.

*(For those of you interested in this kind of thing, the first recorded use of the term “Key Performance Indicator” (KPI) that Google can find is in a book called Wholesaling Management: Text and Cases, edited by Richard Marvin Hill in 1963 – then nothing until 1974… (Google Ngram Viewer: cool or what?))